NATURAL MEDICINE

From Past to Present

Roots of Healing

Until the second half of the 20th century most people in the Western world used some form of natural medicine. With the advent of universal health care and the availability of affordable antibiotic drugs, many common infections were effectively eradicated and the popularity of natural medicines declined. Yet, large swathes of the world's population were untouched by this medical revolution - with up to 80% continuing to rely, in some form, on natural remedies handed down by millennia old traditions.

Where and when these healing traditions began is something of a mystery. Anthropologists suggest that - in response to their environment - early humans developed a 'sensory ecology' based on the appearance, smell, touch and taste of plants, through which they learned to find natural medicines. It has been suggested that people also learned about medicinal plants from studying the interaction between animals and plants.

Bringers of Knowledge

In Ancient Egypt and China mythical ‘bringers of knowledge’ supposedly advanced popular understanding of how the natural world functioned. In Egypt the god Thoth and, in China, Shennong - the ‘divine farmer’ – were said to have delivered knowledge of medicine and agriculture which was passed down through oral legends.

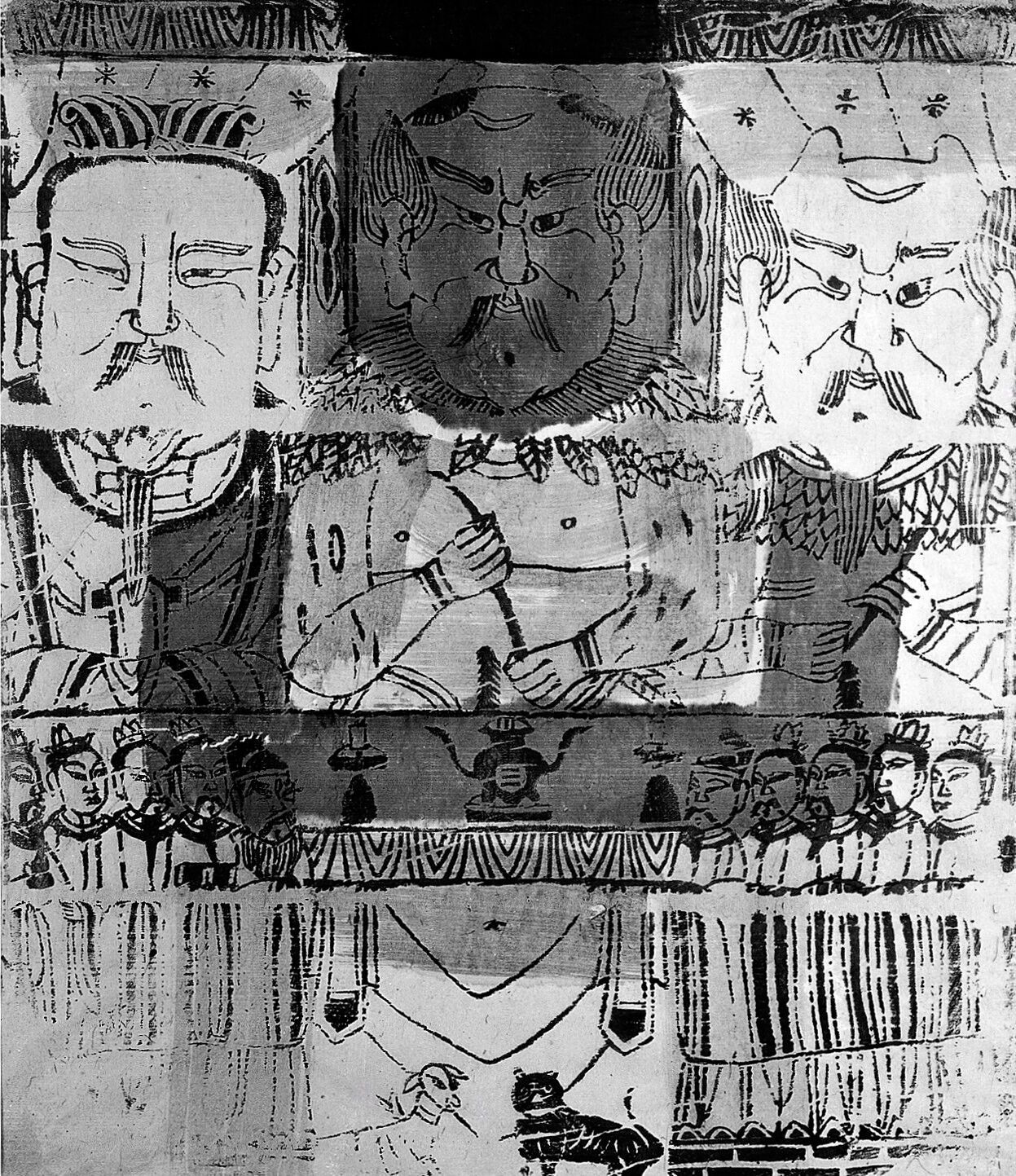

Shen Nung (Shennong), flanked by Fu Hsi (right) and Huang Ti (left) with ten of the most famous Chinese doctors (grouped on either side at foot) Licence: Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) Credit: The Founders of Chinese Medicine. Wellcome Collection. Source: Wellcome Collection.

This oral method of knowledge transmission began to change around 3,000 BC. Ancient Egyptians documented their medical knowledge into hieroglyphic texts in which lie the roots of Greek medicine and alchemy. Commonly misunderstood as the attempted manufacture of gold, alchemy was actually a sophisticated blend of astrology, sorcery and 'primitive' chemistry. The widespread practice of alchemy in natural medicine would continue until the scientific revolution of the 17th century.

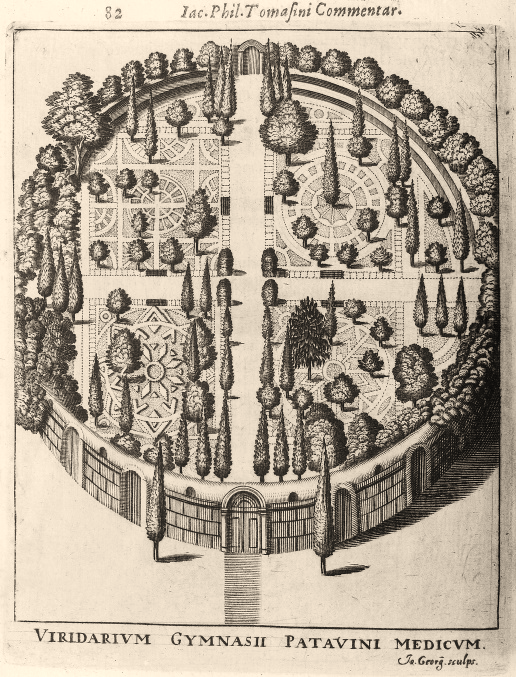

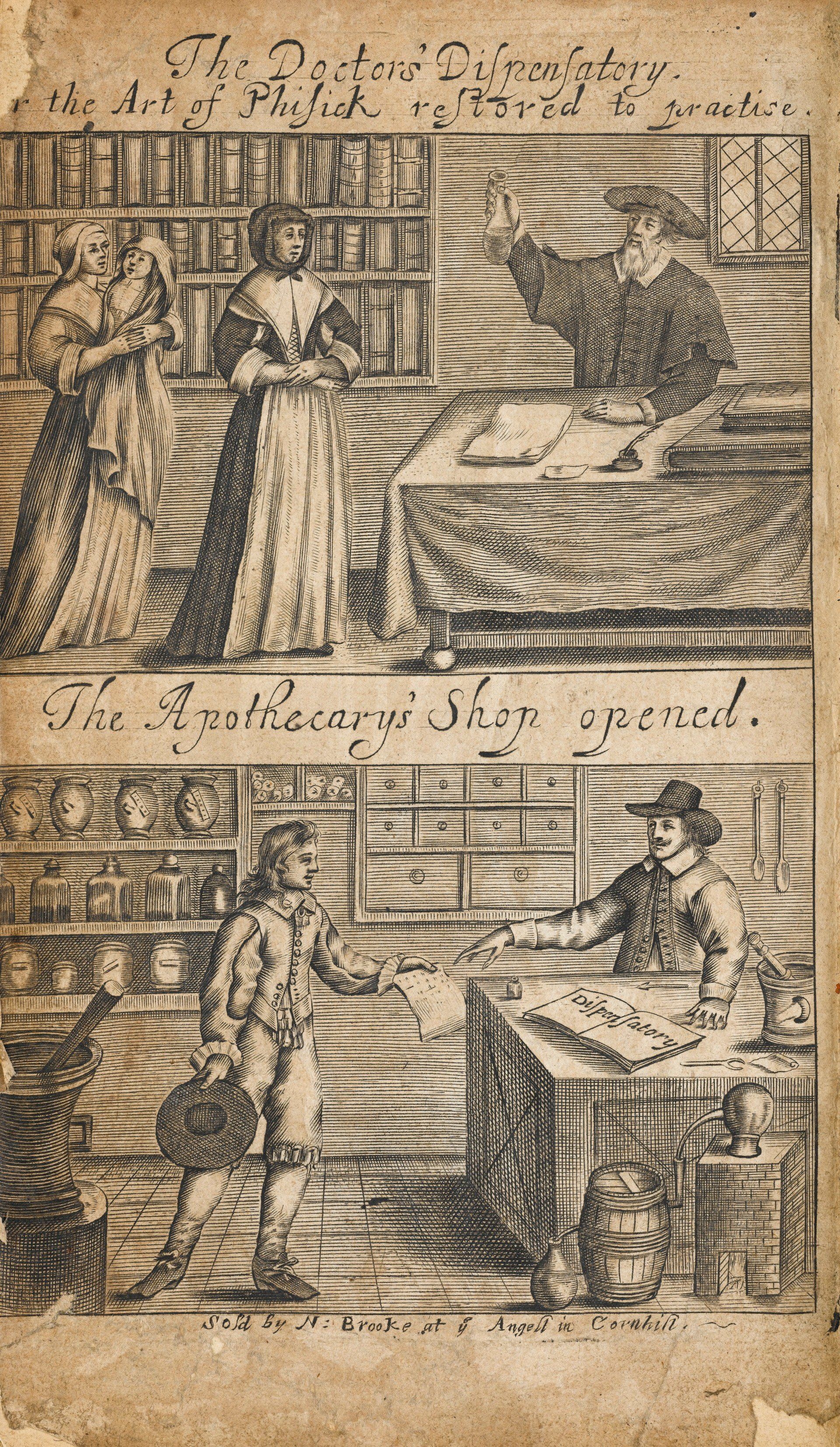

Left to Right: The title page from a Latin translation of Avicenna’s Canon medicinae; Aureolus Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim a.k.a. Paracelsus. (reproduction, 1927, of an etching by Augustin Hirschvogel from 1538) (Wellcome Collection. CC BY 4.0); Botanical garden at Padua. (Wellcome Collection. CC BY 4.0); The Physic Garden, Chelsea: a plan view. Engraving by John Haynes, 1751 (Wellcome Collection. CC BY 4.0)

East to West

Hippocrates (460-370 BC) revived some of the ancient concepts of medicine in his Hippocratic Corpus – which would go on to inspire Western medicine and ethics. His maxim “let thy food be thy medicine and thy medicine be thy food” is of continued relevance, even today - underscoring the inseparability of health and lifestyle. Less so, Hippocrates’ widely believed humoral theory with its notion of the four inter-dependent humors: black bile, yellow bile, blood and phlegm.

Around 2,000 years ago in India, Ayurvedic healers consolidated their medical ideas into three books known as the Great Trilogy (the Caraka Samhita, Sushruta Samhita, and Astanga Hridaya). In China, between 200-250 AD, the Shennong Bencaojing (or Pen-Tsʼao ching) - a three volume work describing 365 herbal medicines attributed to the ‘divine farmer’ Shennong, classified plants according to their therapeutic properties and contained recognizable 'recipes' for producing medicines.

Dioscorides’ De Materia Medica (50-70 AD) provided the first fundamentally Western pharmacopeia. On his travels in the Near and Middle East, the Greek physician Galen (129- 216) encountered a melting pot of medical traditions and cultures. Unani or Greco-Arab medicine, one such system to arise from this cultural exchange, was codified in Avicenna’s the Canon of Medicine (al-Qānūn fī aṭ-Ṭibb) which - written in 1025 - remained in popular use until the 17th century.

In Europe, from the late 15th century onwards, new printing technology allowed for the reproduction and distribution of classic works such as the Canon of Medicine and De Materia Medica, as well as ‘herbals’ - elaborately illustrated books containing detailed information about the cultivation, production and folklore of herbal medicines.

The Birth of Modern Pharmacy

Until the 16th century medicine was almost entirely plant or animal derived. A Swiss born physician, Paracelsus (1493-1541) began to devise 'chemical medicines' (e.g. mercury for the treatment of syphilis). He also insisted that medical texts previously published in Latin were translated into languages which ‘common’ people could understand.

Paracelsus’ ideas were, at first, viewed with suspicion - they contradicted classical humoral theory which had dictated the way in which illness was viewed and treatment chosen. There seemed to be no reason why medicine should re-invent its entire world view, but Paracelsus' ideas began to spark a quiet revolution - in their own way offering a roadmap from medieval ideas of humors and herbalism to modern concepts such as dose and drug design.

Across Europe medicinal plant gardens sprang up - first at Padua and Florence (1545) followed by Leiden (1590) and Montpellier (1593). In 1673 the Apothecaries’ Company founded the Chelsea Physic Garden. In London and Paris scientific societies were formed - rarefied places where the great minds of the day would gather to exchange their findings and put forward bold new scientific theories.

By 1668 the Merck pharmacy was founded in Germany, setting the scene for the mass production of medicines and the birth of a modern pharmaceutical industry.

The Age of Exploration

The drive towards modernity occurred against a backdrop of growing international trade between Europe, Asia and the ‘new world’ of the Americas. As a result of the British East India Company's explorations into Asia, exotic spices and medicines came into the hands of ‘explorer-botanists’, apothecaries, and herbalists. This trade in useful plants was accompanied by a growing interest in what we now call ethnobotany - the anthropological and socio-cultural study of the relationship between plants and the people who use them.

From Plants to Pills

Fresh advances in knowledge during the 18th century would lay the foundations for modern prescription medicines, which would ultimately usurp the place of medicinal plants. In 1796, Edward Jenner (1749-1823) proved that smallpox could be prevented by inoculation with cowpox. Samuel Hahnemman (1755-1843) by a similar principle, devised his ‘law of similars’ – giving rise to homeopathy.

Johann Adam Schmidt (1759–1809) a German-Austrian surgeon would define the term pharmacognosy derived from the Greek words pharmakon (remedy) and gignosco (knowledge) to describe a growing body of research on medicinal plants.

In Victorian England the folk medicine tradition was still thriving, the so-called 'Language of Flowers' (floriography) became a popular idea with its premise that flowers had innate personalities and emotions, harking back to the animistic world view of early healers, but in ‘serious’ circles herbalism was increasingly regarded as quaint and old-fashioned.

The Age of Science

Throughout the 19th century huge strides were made in the understanding of plant chemistry. Dmitri Mendeleev (1834-1907) published the first periodic table in 1869; by 1900 Mikhail Tsvet (1872-1919) had devised chromatography - a technique which permitted the rapid separation and visualization of plant chemicals. Chemists now had tools to categorize medicinal compounds from plants and a growing understanding of their structures and properties.

Meanwhile, Germany had become the major industrial producer of drugs in Europe; mass-producing plant-derived drugs such as heroin and morphine. Merck was a key player, with higher revenue than the major British pharmaceutical companies combined. Willow bark (Salix alba L.) had been recognized as a remedy for aches and fever since antiquity, its active principle salicin was derivatized and synthesized into acetylsalicylic acid by Bayer in 1897 and marketed as Aspirin in 1899. The accepted single compound paradigm of modern Western medicine had arrived.

World War II heralded the mass adoption of antibiotics, with the US shipping industrial quantities of Penicillin - isolated and purified from the mould Penicillium - to wounded soldiers on the battlefields of Europe. The post-war introduction of free universal health care (i.e. the NHS) was yet another blow to the popularity of herbal medicines. Although herbalism continued to be practiced, the incentive to use it was lessened by the availability of free, or heavily subsidized, prescription medicines.

Giant Leaps

In the post-war years sophisticated analytical techniques such as High Pressure Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) could, with just a small starting sample, identify not only the chemical constituents of a plant, but also the structures and conformations of its medicinal compounds. With access to this data, scientific interest in natural medicines increased and the National Cancer Institute (NCI) in the United States embarked upon what remains the largest mass screening of natural products in history - leading to the discovery of the blockbuster drugs Taxol®, vincristine and vinblastine for the treatment of cancers.

Developments in synthetic chemistry, too, meant that compounds could now be modified and synthesized on an even grander scale. Moreover, the discovery of patterns of chemical distribution in different plant families coupled with DNA profiling, allowed for the identification, purification and standardization of natural medicines in a way that had previously been impossible. But there were still risks as well as benefits to be gained from natural medicines. Following a spate of deaths resulting from the misidentification and mislabelling of traditional herbal medicines in the 1990s, a traditional herbal registration (THR) scheme was introduced in the UK to ensure the safety and quality of traditional herbal medicine products (THMPs).

Today natural medicine is a global business, with the herbal supplements market worth an estimated $107 billion in 2017 and Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) $40 billion in China alone. The growing interest in natural medicines has brought with it ethical and moral concerns regarding the ownership of traditional ethnic knowledge (TEK) and the preservation of natural resources. Attempts to address these concerns have been made through global initiatives such as the Convention on Trade in Endangered Species; the Convention on Biodiversity and the Nagoya Protocol.

Ethnopharmacology, the scientific study of the relationship between medicinal plants and the people who use them is perhaps the closest we have yet come to a unifying approach.

A version of this article was originally published on the UCL Spices and Medicine

blog in March 2018